“BUFFALO Bill” CODY’S FATHER ISSAC CODY COMES TO SCOTT COUNTY – AN EARLY STORE LEDGER WHERE ISSAC CODY TRADED

“BUFFALO Bill” CODY’S FATHER ISSAC CODY COMES TO SCOTT COUNTY – AN EARLY STORE LEDGER WHERE ISSAC CODY TRADED

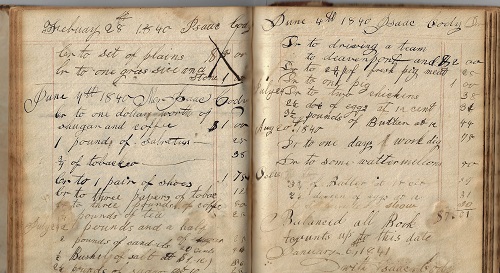

(Iowa - "Buffalo Bill" Cody) Iowa Territory began as a slice of land fifty miles wide on the west bank of the Mississippi River, running north from Missouri to a point near Prairie de Chien, Wisconsin. Encompassing six million acres, this narrow strip came to the United States in 1832 as a cession forced upon the Sac and Fox Nation, a consequence of the Black Hawk War. Divided into two counties, Dubuque in the north and Des Moines in the south, the land was officially opened for white settlement on June 1, 1833, and administered by Michigan Territory. Just three years later, it became the Iowa District of Wisconsin Territory. And in 1838, the Iowa District was separated from Wisconsin and organized as Iowa Territory, stretching from Missouri to Canada and including all of what is now Iowa, Minnesota, and parts of the Dakotas. By this time Iowa had nearly two dozen counties and a white population of about 23,000 settlers, most of whom still lived in the territory’s easternmost counties along the Mississippi. One of the newest of these was Scott County, created in 1837 and named after General Winfield Scott, who had defeated the Sauk war chief Black Hawk five years earlier. This store ledger, one of the earliest surviving examples from anywhere in Iowa, was kept by pioneer merchant Lemuel Parkhurst from the 1820s through the 1840s. It also contains several pages of entries for Isaac Cody--father of Scott County’s most famous native, William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody--from shortly after his arrival in 1840, such that it is also one of the earliest surviving records of the Cody family in Iowa.

Scott County was carved from Dubuque, Muscatine (1836), and Cook (1836) counties, the latter now extinct. Although the county was established in 1837, a long dispute between Davenport and neighboring Rockingham--including three contested elections--kept the former from being declared county seat until 1840. Just seven years later, Rockingham was annexed by Davenport and ceased to exist as a municipality. Davenport was and remains the population and commercial center of Scott County, but other towns were established at about the same time.

Among the most important of these, particularly in Iowa’s subsequent state history, was LeClaire, situated about 15 miles upstream from Davenport where the Great Bend of the Upper Mississippi begins to make its deep turn to the west. LeClaire was named after Antoine LeClaire, a Métis trader of First Nations and French Canadian descent. As part of their 1832 settlement after the Black Hawk War, the Sac and Fox had given LeClaire 640 acres here, seemingly out of respect and friendship.

They likewise gave 640 acres at the site of modern Davenport to his wife, Marguerite, who was the granddaughter of a Sauk chief. LeClaire had lived among the tribes since boyhood, either as an employee of the American Fur Company or as an interpreter for the government. He and Marguerite built a home on the site of her gift, where the agreement of 1832 was signed, and LeClaire founded Davenport there in 1836. He had begun planning a town on the site of his own gift as early as 1833, but he was unable to plat the land until 1837. And so the Parkhursts got there first.

Four Parkhursts--brothers Eleazer and Sterling, with their nephew Waldo and Sterling’s son Lemuel--settled in the area just south of LeClaire’s grant from 1834 to 1837. Originally from Milford, Massachusetts, like all of his Iowa kinsmen, Eleazer was the first to arrive. He purchased a claim along the Great Bend and had a cabin built there in February 1834, the first white settlement in the area of what would become LeClaire. Sterling followed soon after, with Waldo and Lemuel arriving by 1837. In 1836, before Antoine LaClaire had finished platting his own site, Eleazer had

successfully petitioned for a post office. The office was named Parkhurst and Eleazer himself was appointed postmaster, whereupon he and fellow pioneer Col. T. C. Eads began laying out a town of their own. Over the next few years, LeClaire and Parkhurst (its name was changed to Berlin in 1842) grew into adjacent demographic and commercial rivals. Finally, in 1851 the last remaining strip of land between the two villages was sold and laid out as building lots, after which LeClaire was incorporated and Parkhurst folded into its city limits.

In 1839, Lemuel Parkhurst opened the first store in either village, housed in a small stone building at Parkhurst later owned by his uncle, William Gardner. A year later, Eleazer and Waldo opened another store in a stone structure built by Eleazer. Their firm was active until 1849, when it seems to have been dissolved by mutual agreement. Waldo, however, soon opened another store that he operated well into the 1870s. We suspect that this small ledger, which combines accounts for labor performed as well as for store purchases, was kept by Lemuel at his first store. Lemuel and his father, Sterling, came to Iowa from Ontario County, New York, where Sterling had moved his family in the 1820s. About the first third of the ledger (25-30 pages with dates from 1826 to 1836) contains accounts of labor performed for people with connections to Ontario. This includes Hubbard Parkhurst, Lemuel’s older brother who was already married and did not accompany his father to Iowa, and William Gardner, who had married Lemuel’s sister, Ann, in Ontario in 1826 and did not join Sterling and Lemuel in Iowa until 1840. Two different hands made entries during this period, likely either Sterling and Lemuel or Hubbard and Lemuel.

Entries dating from 1837 to 1851, about two-thirds of the ledger, are all from Scott County and offer rich details of life on the Iowa frontier. Many of the entries are for manual labor and odd jobs that Lemuel performed for neighboring pioneer families. Born in 1818, he was only 19 years old when he came to Iowa, and much of the work that he did was commensurate with what was expected of young men in this frontier time and place: splitting beams; hiring out for work with a horse or teams of oxen; repairing shoes; making a pair of pantaloons; sawing; hauling loads of stone, lumber, and produce; and hoeing, threshing, and mowing. He seems to have regularly sold

large quantities of agricultural produce: bushels of potatoes, wheat, oats, beans, and corn. Perhaps the most interesting records are for supplies, dry goods, and merchandise sold at the store: many of these entries are for staples such as salt, flour, sugar, honey, butter, eggs, coffee, and tea, as well tobacco and whiskey, but he also recorded sales of fresh beef and pork and live chickens (whether for eggs or meat). Not surprisingly given the time and place, there was only a limited range of manufactured goods: a chopping knife; boxes of pills and a bottle of bitters; a copper pot; factory cloth, calico, flannel, and stocking yarn; shoes; candles; a set of carpentry planes; nails, bolts, and screws; door trimmings; and a saddle and bridle. Some two dozen customers are ientified in this part of the ledger, all among the pioneers of eastern Iowa. None is better known today than Isaac Cody, if only for the exploits of his second son, who as a showman to rival P. T. Barnum became a household name throughout the United States and Europe.

No single person contributed more to the creation of a Wild West mythology than William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Today it is impossible even to sort the fact from the myth in Cody’s own life. Yet however many of Cody’s tales and recollections are true, he seems to have inherited his sense of adventure--if not wanderlust--from his father, Isaac, who came west to Iowa Territory in late 1839 and settled for several years in Scott County. Cody first established a business trading with Indians near Davenport, and after a year had saved enough money to purchase a small house at LeClaire. He also made a homestead claim on a piece of land two miles west of town where he built a four-room log house. Six children were born there to Isaac and his wife, Mary, including William in 1846. The Cody family pulled up stakes and left for Kansas in 1854. Just a few months later, Isaac was stabbed twice in the chest with a Bowie knife while making an anti-slavery speech in Leavenworth. He never fully recovered and died of pneumonia in 1857. William went to work to help support his mother and sisters, finding his path to fame. Three pages in the Parkhurst ledger

are devoted to Isaac Cody’s accounts.

The ledger itself is entirely legible, though its boards and spine are quite worn and fragile. There are no more than a handful of surviving store ledgers or account books from these earliest years of Iowa’s territorial period, and we trace no other examples ever having been offered at auction or in the trade.

Relevant sources:

Bremer, Jeff 2017 “Land Was the Main Basis for Business": Markets, Merchants, and Communities in Frontier Iowa. The Annals of Iowa 76(3):261-289.

Downer, Harry E. 1910 History of Davenport and Scott County Iowa: Illustrated. Volumes I . S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, Chicago.

Beck, Robin – Primary Sources

Goodwin, Cardinal 1919 The American Occupation of Iowa, 1833-1860. Iowa Journal of History and Politics 17(1):83-102.

Mahoney, Timothy R. 1990 River Towns in the Great West: The Structure of Provincial Urbanization in the American Midwest, 1820-1870. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.