George Scott Cabinet Card Photograph of Chief Big Head, Accompanied by a Signed Letter, From Photographer George W. Scott to Collector Charles F. Fish.

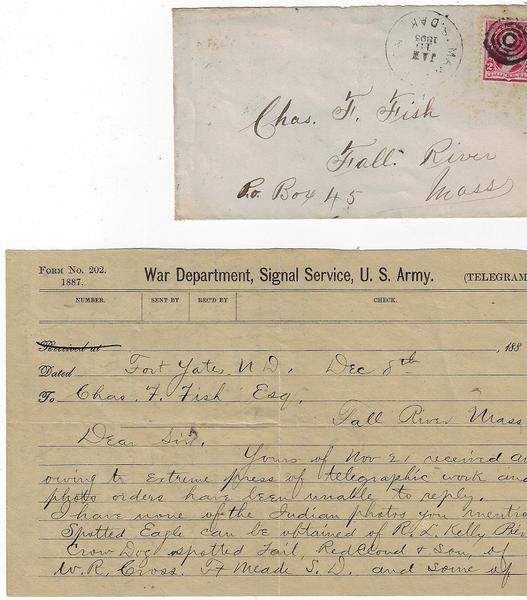

Big Head - Fort Yates, N.D. [Cabinet card circa 1888-89]; Letter dated December 8,188_. [2]pp. autograph letter, signed, on a 5 x 8 inch telegram form, with envelope postmarked Jan 19, 1895; albumen cabinet card photograph, 5 1/4 x 4 inches, on a slightly larger mount. Letter: old folds, envelope with stamp and multiple postmarks. Very good. Cabinet card: A.e.g. Light foxing. Pencil caption below photo, extended caption in pencil and ink on verso. Very good.

Big Head :

“Chief Big Head, Pahtanka or Nasula-Tanka was born about 1838 and died in 1889.

Big Head, the head chief of the Cut Head band of the Yanktonais, was born in the winter called Wičhapi Okhičamna, the Moving of the Stars and the time of the great smallpox year called Wičahaŋhaŋ. In this year the stars did not fall to the earth as they did in 1834 and ’37, but the movement of the stars went on in the heavens with flashes and great disturbances all during the night. This is said to have happened in 1830, according to the record of Little Dog, a Huŋkpapȟaya.

Big Head, commonly called Pažipa, was influential in his band. He had good judgment, was kind and truthful. He was born in Minnesota. He had 25 families and lodges in his camp. The Yanktonais lived in the Dakota Territory east of the Missouri River, east to the Misapplies and North to the Apple Creek Valley which they considered their homeland.

Big Head (Pahtanka or Nasula-tanka, which means Big Head or Big Brain), son of a Yanktonais Chief with the same name and his wife Turns Back (ca. 1814), was born about 1838. The 1858 treaty with the Yanktons (they had agreed to a massive land cession of 11 million acres, nearly 23 percent of the present state of South Dakota) infuriated the Lakotas and Yanktonais. This land cession directly affected the Yanktonais, whose primary bison hunting grounds were east of the Missouri River. At Fort Pierre, Lakotas demanded that the federal government revoke the 1858 treaty and stop the Yankton treaty payments. Further up the river, Upper Yanktonai chief Big Head (father), who had a reserved attitude toward the whites, refused the treaty and to accept treaty annuities. He, accompanied by eighty warriors, sharply informed Indian Agent Alexander H. Redfield that the Yanktons had no authority to cede these lands, for they belonged to all Sioux.

In 1863, the older Big Head and the Yanktonais were involved in the punishment campaign following the Minnesota Uprising. He survived and was captured at the Massacre of White Stone Hill located near Kulm, North Dakota the following year. Chief Big Head and Chief Two Bears with other survivors were taken to Fort Randall, South Dakota and held prisoner for two years.

On 3 September 1864, they were engaged in the Battle of Whitestone Hill, where General Alfred Sully surrounded a Sioux hunting encampment, containing some 500 lodges, mainly Yanktonais under the leaders Two Bears, Little Soldier, and Big Head and Hunkpapa under their leader Black Moon. Some Santee were also present. Sully attacked the Sioux and massacred mostly women and children because the men were out hunting. Then Sully rounded up the friendly bands of Little Soldier and Big Head, about 30 men and 90 women and children in all, who were taken as prisoners of war to Crow Creek Agency, where many died from starvation. Some Winter Counts report the death of a Dakota called Big Head, who was taken prisoner by soldiers. This must have been the older Big Head.

After the death of his father, the son took the name Big Head. Big Head and his band were captured by General Sully at White Stone Hill. They were brought down to Old Fort Sully and, after the Treaty of 1868, he and part of the Cut Head bands were placed at Standing Rock, Dakota Territory. Remnants of the bands of Cut Heads can be found at Devil’s Lake, North Dakota; Poplar, Montana; and Crow Creek, South Dakota. During the battle of White Stone Hill, Big Head became separated from his wife and was reported killed. She had a small son. Later, she became the wife of Waanataŋ or Charger, a Mnikowožu chief. When a reunion of the nations took place, Mrs. Big Head saw her former husband alive and well at a dance. She told Waanataŋ she wished to return to her former husband. Waanataŋ felt pretty bad but acted the man. He loaded her horses with costly presents and leading a horse for a present to Big Head, he led the horse of his wife and returned her to Big Head. The chiefs shook hands and became loyal friends.

On October 20 and 28, 1865, the U.S. made treaties with Hunkpapa and Yanktonai at Fort Sully. The signers included Two Bears, Big Head, Little Soldier, and Black Catfish. In these treaties, the Indians agreed to cease all hostilities with U.S. citizens and with members of other tribes. They also agreed to withdraw from overland routes through their territory. They accepted annuity payments, and those who took up agriculture would receive implements and seed.

Three years later, in 1868, Big Head was a signatory to the “Fort Laramie Treaty,” which was actually signed at Fort Rice by the Yanktonais. In the following year, the Grand River Agency (moved and renamed Standing Rock in 1874) was established.

Big Head and his Cut Head band still roamed the upper Missouri and even the Milk River region in Montana in the 1870s. His band settled – at least for a time – at the Fort Peck/Poplar River Agency. In 1872, Big Head was one of the Yanktonais leaders who travelled to Washington.

The Yanktonais head chiefs – Medicine Bear, Black Eye, Two Bears, Big Head, and others – wanted to negotiate the acceptance of their wish to stay in Montana at the new Milk River Agency (later Fort Peck). In the end they failed.

In 1876, there were only a few Yanktonais in the battle of the Little Bighorn. It is known that a small group of Yanktonais from Fort Peck – Thunder Bear, Medicine Cloud, Iron Bear, Long Tree, and some women – joined Sitting Bull’s camp to hunt and trade. At that time, the Yanktonais skirmished a lot with tribes like the Gros Ventre, the Assiniboines, and the Crows.

In 1876, Big Head was in the Battle of Little Bighorn (Greasy-Grass). After the Battle; he took refuge in Grandmother’s country (Canada) with other chiefs and bands. According to oral history, Sitting Bull told the chiefs to scatter in their return to the United States so they would not be killed prior to his surrender. In the early 1880s, Big Head, who called himself Felix Big Head, moved to Standing Rock, where he had 17 lodges and 168 people under his care in the northern part of the reservation .

On the Standing Rock Reservation and under the tutelage of Agent McLaughlin, Big Head, who had evolved into one of the main Standing Rock leaders, belonged to the strong supporters of the Edmunds plan. Taking part in reservation politics, Big Head got his hair cut and, in 1888, he went to Washington, dressed in a suit, as part of the Sioux delegation to negotiate the cession of Sioux lands. On this occasion (and with the support of Agent McLaughlin) the Sioux successfully fought against the selling out of reservation land.

That would change in 1889. When the new Crook commission convened its hearings at Standing Rock in July 1889, Gall, John Grass, Mad Bear, and Big Head were prepared to speak out against the second Sioux bill as they had in Washington. But Major McLaughlin had switched positions and, in private conversations, he turned over Grass, Mad Bear, and Big Head.

Grass, “with the facility of a statesman,” argued convincingly on behalf of the new position. Gall, Mad Bear, and Big Head gave shorter but likewise influential speeches on behalf of the 1889 Sioux bill, which enraged Sitting Bull. These leaders compelled many undecided agency Indians to vote for the new bill. Gall and Mad Bear later regretted their decision.

Major James McLaughlin, Indian Agent at Standing Rock for a time, thought very highly of him as a man. During the negotiation of the treaty of 1889, Big Head worked hard among his people to hold on to their land and not dispose of any more of it in treaties until the previous treaties were fulfilled.

The commissioners from Washington, consisting of Governor Foster of Ohio, Captain Pratt, and General Crook, all threatened war if the Indians did not consent. Big Head said:

“It is no use to talk about the old times. The Government has made treaties two or three times and the Commissioners never tell lies. They told us at Ft. Rice (1868) that they would give every family a yoke of oxen, a cow, a wagon and other things and said nothing about land being selected. The interpreter who explained the treaty to us never told us that way. The Commissioners who were here last fall were asked for the same things and for light wagons, too, and they said they would ask the Great Father for them. We would like to hear about this last treaty. The Government sends more annuities and provision to other Indians than it does to us because the others are mean and bad. At Cheyenne they have more goods and supplies. An Indian who came from there told me this. He may have fooled me, but he told me so. The Indians here did not get enough clothes. One blanket to each man and woman is not enough for the winter time. We don’t know yet which we would prefer—blankets or citizen’s clothes. I suppose we are going to get some working cattle but they are too slow. We ought to have mules and wagons. There is no use to ask for horses or ponies as the Government would think we intended to run away with them. One mule and a good cart would be good but we couldn’t haul logs or wood or hay. We ought to have a strong wagon and a pair of mules. They said all this land of the Indians could be taken by conquest if the Indians did not submit. I was there at that time, and had just returned from Hampton, Virginia the year before the treaty, so could understand both sides, the Indians’ and the whites’.” We have been farming down below (from some seven to fifteen miles south of the Agency on the east side of the river) for many years and we intend to farm there again, but we don’t to go to Cheyenne or Ft. Thompson (Crow Creek), though the Agents and Indians there are trying to get us to go. We have heard this for a long time. I like to hear you talk. I think you are going to help us. You don’t allow anyone to buy wood. That’s the way we want it. The whites below us cut our wood and when the Indians say anything they tell us the land there belongs to the Government. Parkins (in charge of Indian Trader’s Store) sells his wood to the Government too cheaply. He ought to charge a big price and then we could get a good price, too. We would like to have a Catholic Priest across the river and a school over there.”

They felt opposed to any more treaties. They trusted their chiefs to hold out and not give in to the threats being used in the arguments. Big Head further stated:

I heard General Crook say, “This country you want to keep so bad is not all good. About half of it is badlands.”

I heard the crowd murmuring, “Then why do they want it so badly?”

General Crook went on to say they could take this land by conquest and ship all the Indians down south as slaves. This was only eight years after the Indians had surrendered to the United States government. Their guns and horses had been confiscated. The reservation was a semi-arid country with hardly any rainfall and they were depending on the government for rations since all the game was gone. There was nothing left to subsist on, only a few yokes of oxen issued by the government with which to till the soil, but most of these were wild and unmanageable. It seemed to be one of the darkest hours for the Indians. How could there be a war? The Indians had been dispossessed of all their guns and horses and were hemmed in on a half desert reservation. John Grass and Gall, under McLaughlin’s advice, were the first to consent to the conditions of the new treaty. All the head chiefs were taken to Washington where they sullenly sighed away their last hunting grounds, the Badlands, where there was a natural game reserve and where there would always be game. After the return from Washington, the chiefs were down-hearted.

The Indians did not want to dispose of their land. Big Head only lived a month or two after returning and died of grief. Upon his death in 1889, he was buried in the Cannon Ball area. (From: Native Heritage Project)

George Scott -

Born and raised in Georgetown, District of Columbia on March 21, 1854 Scott served in the signal corps and weather bureau through the War Department. “He then joined the U.S. Signal Service, and after passing through its school of instruction he was stationed successively at Pittsburg, Washington, Philadelphia, New York, Duluth, Bismark, N.D., Fort Bennett and Deadwood S.D. where he quit the service and engaged in the photograph business in 1883. He passed four years in the business in that city, and then reentering the signal service was stationed at Omaha and from there in 1891 to reopen the abandoned station at Yankton and take charge of the weather bureau at that place, where he remained three years, going thence to Des Moines, Iowa, for a short time and finally in 1894 coming to Lander as the head of the bureau of that brisk, young city. Soon after coming here he started a photographic business and leased the telegraph line and has conducted both of these establishments almost continuously since then. He has the only photograph gallery for the patronage of Lander and many miles of adjacent territory, and by his skill and attention to business has secured a large and profitable trade.” (from: Wikimedia Commons)

Autograph Letter Signed from Scott to Charles F. Fish of Fall River, MA. 2 pages, written on an Army Signal Service telegraph blank. In part: "I have none of the Indian photos you mention. Spotted Eagle can be obtained of R.L. Kelly, Pierre, SD. Crow Dog, Spotted Tail, Red Cloud & son, of W.R. Cross, Ft. Meade, S.D. and some of balance any way of Mr. D.F. Barry, West Superior Wis. The only photos of note that I have aside from the principal chiefs, Gall, Rain in the Face, Sitting Bull, John Grass, Mad Bear, and Big Head, are Wolf Necklace (decorated with 9 scalps), Hairy Chin, Long Dog, Mrs. Two Bear & papoose, "Scarlet Woman" (mother of the new Messiah), a miniature of Sitting Bull's Ghost Dance, besides others in native dress, dance costumes &c &c." Fort Yates, ND, 8 December [1894]. With envelope addressed to Fish postmarked Mandan, SD, 19 January 1895.

Charles F. Fish (1859-1940) traveled west in 1875. He became so enamored by the west he started cllecting western photography. In particular images of Native Americans, wild west showmen, cowboys and mountain men. His extensive collection included many early images and was exhibited at the Museum of natural History in New York in 1921.