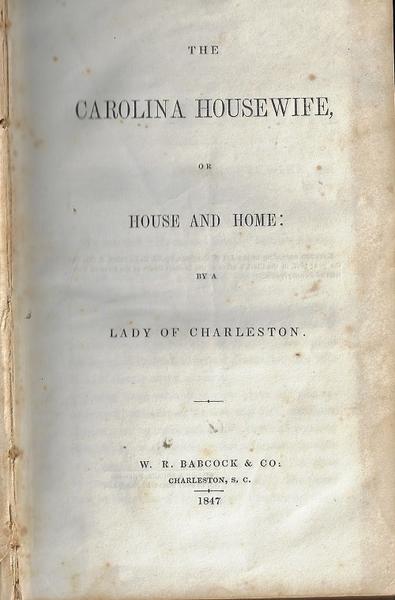

ONE OF THE FIRST THREE REGIONAL AMERICAN COOKBOOKS. THE CAROLINA HOUSEWIFE, OR HOUSE AND HOME: BY A LADY OF CHARLESTON

ONE OF THE FIRST THREE REGIONAL AMERICAN COOKBOOKS

THE CAROLINA HOUSEWIFE, OR HOUSE AND HOME: BY A LADY OF CHARLESTON

14). (Extremely Rare Cookbook) Rutledge, Sarah. Few American cookbooks are as genuinely iconic as THE CAROLINA HOUSEWIFE, OR HOUSE AND HOME: BY A LADY OF CHARLESTON. Few have offered as creative a presentation of any region’s cuisine. Fewer have so epitomized the political and economic tensions of its era. And fewer still have featured as unlikely an author as Sarah Rutledge, its titular Lady of Charleston. Rutledge’s CAROLINA HOUSEWIFE is the last of what are widely recognized as the first three regional American cookbooks, together with Mary Randolph’s The Virginia House-Wife (1824) and Lettice Bryan’s The Kentucky Housewife (1839). It is the first cookbook to feature rice as an American staple and the first to focus on the foodways of the Lowcountry; Randolph’s work stands as a record of early foodways in the Tidewater country, Bryan’s in the Bluegrass region.

First published at Charleston in 1847 and reprinted twice during the decade before the Civil War, all antebellum editions of The Carolina Housewife are extremely rare in the antiquarian market. We locate no copies of the first edition in its original binding, as here, offered in more than a century. The Carolina Housewife was published anonymously, as ladies of Charleston were only expected to have their names in print three times: when they were born, when they wed, and when they died. Yet it was hardly a secret among her family and friends that the author was Miss Sarah “Sally” Pinckney Rutledge (1782-1855), daughter of Edward Rutledge--a signer of the Declaration of Independence--and niece of another South Carolina signer, Arthur Middleton. She was as close to royalty as one could be in the post-revolutionary South. During her youth, Rutledge lived in England with the family of her father’s legal partner, Thomas Pinckney, who was U. S. minister to the Court of St. James (i.e., the U. S. ambassador to the United Kingdom). On returning to the United States, she would spend the remainder of her 73 years in Charleston, whether at her family’s home at the corner of Broad and Orange streets (which still stands today as the Governor’s House Inn); at the home of her brother, Henry Middleton Rutledge; or at various locations in town with her widowed stepmother, Mary Rutledge, and cousin, Harriet Pinckney

All of these homes and their different kitchens--and different kitchen staffs--undoubtedly gave Rutledge a broad range of experience with Lowcountry foodways, and in 1847, at the age of 65, she produced the first edition of her famous cookbook, featuring about 550 recipes. Reprinted in 1851 and 1855, it promised its readers “principally receipts for dishes that have been made in our own homes, and with no more elaborate abattrie de cuisine than that belonging to families of moderate income: even those dishes lately introduced among us have been successfully made by our own cooks” (1847, p. iv). Nearly a hundred of these dishes include corn or rice, including the first published recipe for Hoppin’ John, a traditional Lowcountry favorite of long-grain rice, black eyed peas, and salt pork. There are more than five pages of tomato recipes, including directions for stewing, frying, baking, pickling, and preserving this distinctly American product. Her recipe for “Macaroni al la Napolitana” was among the first published in America combining the tomato

with a pasta. There are recipes for cooking tomatoes in omelets and with okra, one for “Knuckle of Veal with Tomatoes,” and another for “Baked Shrimps and Tomatoes.” Her rice dishes, besides Hoppin’ John, include rice crumpets, waffles, sponge cake, flummery, blancmange, golden crusted casseroles, and a “Poor Man’s Rice Pudding.” As Karen Hess writes, “Miss Rutledge recognized the peculiar genius of South Carolina cookery and set about to record it” (1992:86).

Yet Rutledge likely prepared few of these Lowcountry dishes herself, and certainly not on a regular basis. Instead, most all of the meals that she and her family enjoyed, as ranking members of Charleston’s elite, would have been prepared by enslaved women. Indeed, Rutledge’s family owned a large rice plantation near the city that enslaved more than fifty people. The great majority of enslaved domestic workers could neither read nor write. As such, The Carolina Housewife was written not for them, but for their mistresses, the genteel white women for whom they labored as

property. And many of the recipes described in its pages were West African in origin, including those for bennie (sesame) soup, two different okra soups, groundnut soup, and even the traditional Hoppin’ Johns. This cookbook, so famous for its original presentation of southern cuisine, thus documents the shaping of that cuisine by African ingredients and tastes. Such is true for each of the southern “Housewife” texts: the African recipes they recorded ironically came to define what

it meant to be southern. According to Sarah Walden, “The physical and intellectual labor of slaves made possible the observable tastes of the white slaveholding elite” (2018:96). Each of these three cookbooks is extremely rare, particularly in the first edition. We trace no sale or auction records for firsts of either The Carolina Housewife or The Kentucky Housewife; two badly worn copies of The Virginia House-Wife appeared in 2011 and 2016, bringing $1320 and $2125, respectively. Blank ffep and two blank rear end papers cut vertically. An important book--and in remarkably nice, original condition.

Relevant sources: Hess, Karen. 1992 The Carolina Rice Kitchen: The African Connection. University of South Carolina Press, Columbia; Rutledge, Anna Wells. 1979 Introduction. In The Carolina Housewife, A Facsimile of the 1847 Edition, pp. vii-xxvi. University of South Carolina Press, Columbia: Beck, Robin. Primary Sources; Walden, Sarah W. 2018 Tasteful Domesticity: Women's Rhetoric and the American Cookbook, 1790-1940. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh