The Balance and Columbian Repository - The Hamilton - Burr Duel

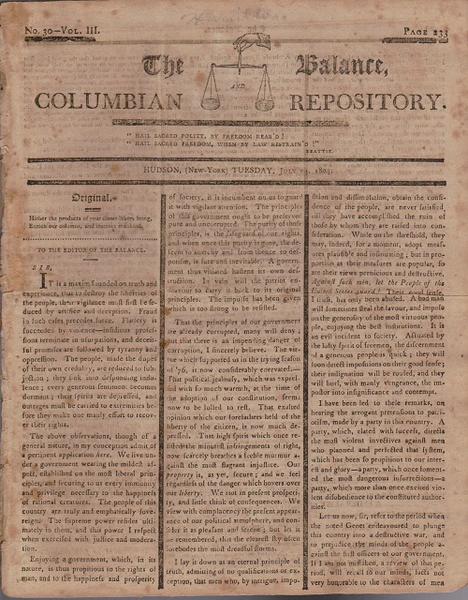

Published in Hudson, New York by Sampson, Chittenden and Crosell, THE BALANCE AND COLUMBIAN REPOSITORY was published from 1801 – 1807. It was a 10 ¾” x 8 ½” 3 columned paper which highlighted some of the news of the day. The eight papers, pages 233 – 296, beginning on Tuesday July 24, 1804 – No. 30, Vol. III thru Tuesday September 11, 1804 – No. 37, Vol. III, are the complete set concerning the duel between the former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and the sitting Vice President Aaron Burr, on July 11, 1804. At the Heights of Weehawken, New Jersey, Burr shot and mortally wounded Hamilton, who was carried to the home of William Bayard on the Manhattan shore, where he died on July 12, 1804.

The July 24th Balance and Columbian Repository has a section titled Death of Hamilton From the Evening Post to The American Public; A Tribute; and Funeral Obsequies. The July 31st edition has The Funeral Oration of Governor Morris at the Funeral of Gen. Hamilton at Trinity Church; the Death of Hamilton From the Evening Post. Correspondence Which Preceded the Late Fatal Duel, and The Wreath – From the American Citizen – The Grave of Hamilton. The Aug. 7th edition prints a letter under the section Monitorial to the Editor of the Commercial Advertiser from J.M. Mason Concerning Hamilton. The August 14 issue has an editorial titled Gen. Hamilton. The August 21 issue under the category of Editor’s Closet has an article titled General Hamilton and a second titled Hamilton from the Boston Repertory. On August 28 under the heading of Monitorial are excerpts of Rev. Mr. Nott’s incomparable Sermon on The Death of Gen. Hamilton Delivered at Albany. On September 4th, the paper under the section titled Bee Fibs gave information concerning Hamilton’s other duals plus under the section Monitorial were Extracts From the Rev. E. Nott’s Sermon on the Death of General Hamilton. The final paper, September 11th under the section Monitorial is an Extract from the Rev. E. Nott’s Sermon on the Death of General Hamilton.

This being one of the most famous personal conflicts in American history, the Burr-Hamilton duel arose from long-standing political and personal bitterness between the two men. Hamilton’s opposing Burr’s ascension to the U.S. Presidency in 1800; his journalistic defamation of Burr’s character during the 1804 New York gubernatorial race and the conflict between Democratic-Republicans and Federalists. Animosity ran high between the two men. In a January 4, 1801 letter a bitter Hamilton wrote “Nothing has given me so much chagrin as the Intelligence that the Federal party were thinking seriously of supporting Mr. Burr for president. I should consider the execution of the plan as devoting the country and singing their own death warrant. Mr. Burr will probably make stipulations, but he will laugh in his sleeve while he makes them and will break them the first moment it may serve his purpose.” In a private letter to Supreme Court Justice Rutledge, Hamilton argued against Burr’s character as being “suspected on strong grounds of having corruptly served the views of the Holland Company...his very friends do not insist on his integrity...he will court and employ able and daring scoundrels...his conduct indicated (he seeks) Supreme power in his own person...will in all likelihood attempt a usurpation.”

Nor was this Hamilton or Burrs first duels. In at least 10 shotless duels prior to this fateful dull Hamilton had taken part. In 1779 with William Gordon, 1790 with Aedanus Burke, 1792-1793 with John Francis Mercer, 1795 with James Nicholson, 1797 with James Monroe, 1804 with Ebenezer Purdy / George Clinton and according to Hamilton, there had been at least one other duel with Burr. Burr stated that there had been two previously with Hamilton.

According to historian Joseph Ellis, his account of the duel was “Hamilton did fire his weapon intentionally, and he fired first. But he aimed to miss Burr, sending his ball into the tree above and behind Burr’s location. The bullet only skimmed Burr’s ear. In so doing, he did not withhold his shot, but he did waste it, thereby honoring his pre-duel pledge. Meanwhile, Burr, who did not know about the pledge, did know that a projectile from Hamilton’s gun had whizzed past him and crashed into the tree to his rear. According to the principles of the code duello, Burr was perfectly justified in taking deadly aim at Hamilton and firing to kill, But did he? What is possible, but beyond the reach of the available evidence, is that Burr really missed his target, too, that his own fatal shot, in fact, was accidental.”

Dr. David Hosack, Hamilton’s attending physician, in a letter to William Coleman wrote the following account, “When called to him upon his receiving the fatal wound, I found him half sitting on the ground, supported in the arms of Mr. Pendleton. His countenance of death I shall never forget. He had at that instant just strength to say, ‘This is a mortal wound, doctor’, when he sunk away, and became to all appearance lifeless. I immediately stripped up his cloths, and soon, alas I ascertained that the direction of the ball must have been through some vital part. His pulses were not to be felt, his respiration was entirely suspended, and, upon laying my hand on his heart and perceiving no motion there, I considered him as irrecoverably gone. I, however, observed to Mr. Pendleton, that the only chance for his reviving was immediately to get him upon the water. We therefore lifted him up, and carried him out of the wood to the margin of the bank, where the bargemen aided us in conveying him into the boat, which immediately put off. During all this time I could not discover the least symptom of returning life. I now rubbed his face, lips and temples with spirits of Hartshorn, applied it to his neck and breast, and to the wrists and palms of his hands, and endeavored to pour some into his mouth. ....Soon after recovering his sight, he happened to cast his eye upon the case of pistols, and observing the one that he had had in his hand lying on the outside, he said, “Take care of that pistol; it is undischarged, and still cocked; it may go off and do harm. Pendleton knows” (attempting to turn his head towards him) ‘that I did not intend to fire at him’ Yes’, said Mr. Pendleton, understanding his wish, “I have already made Dr. Hosack acquainted with your determination as to that’ He then closed his eyes and remained calm, without any disposition to speak; nor did he say much afterward, except in reply to my questions. He asked me once or twice how I found his pulse; and he informed me that his lower extremities had lost all feeling, manifesting to me that he entertained no hopes that he should long survive.”