The Platte River Bridge Tragedy - An Early Report from Leavenworth

THE PLATTE RIVER BRIDGE TRAGEDY: AN EARLY REPORT FROM LEAVENWORTH -

AN IMPORTANT ACCOUNT OF THE CIVIL WAR IN THE WEST WHEN UNION SUPERIORITY IN KANSAS AND MISSOURI WAS FAR FROM SETTLED.

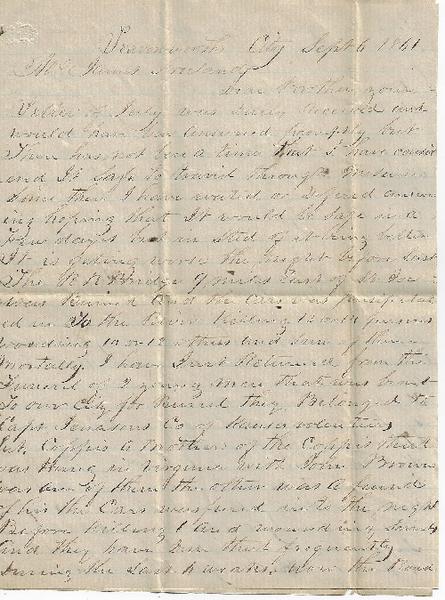

(Kansas and Missouri--Civil War) Freeland, William. An autographed letter signed by William Freeland discussing the Platte River bridge tragedy and war preparations in Leavenworth, Kansas. Leavenworth City, Kansas, September 6, 1861. 4 pgs. on a single folded sheet. Old folds, light edge wear, paper lightly tanned; with stamped and postmarked cover. Overall very good.

The question of whether Kansas would enter the Union as slave state or free exposed once and for all the incommensurability of two Americas, each with a violently different understanding of personhood and liberty. Bleeding Kansas earned its name during the five years prior to the Civil War, from John Brown’s massacre of five pro-slavery settlers at Pottawatomie in May 1856 to the capture and shooting of eleven Free-Staters by Charles Hamilton’s gang near Trading Post exactly two years later in May 1858. After war engulfed the nation, the conflict in Kansas and neighboring Missouri witnessed some of the most brutal and intense fighting anywhere in either the eastern or western theaters. Much of the violence was perpetrated by bands of guerrillas operating outside the conventional rules of warfare, both pro-Union Free-Staters from Kansas and pro-Confederacy Border Ruffians or Bushwhackers from Missouri. Among the most vicious of these atrocities took place on the night of September 3, 1861, when Bushwhackers attacked a Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad bridge over the Platte River near St. Joseph, derailing a passenger train carrying civilians and Federal soldiers bound for Fort Leavenworth.

This letter, written from Leavenworth City just three days later, provides an early notice of the attack and offers a first-hand glimpse of conditions in this pro-Union town less than a year into the war.

Missouri was a slave state until the passage of the 13th Amendment, yet like Kentucky it never formally seceded from the Union. Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson was a vocal Confederate sympathizer, however, and in the early months of the conflict he sought to throw Missouri over to the southern cause. When Union General Nathaniel Lyon captured the capitol of Jefferson City in July, Jackson and his pro-slavery allies fled to Neosho in the southwest corner of the state, where they briefly organized a government-in-exile before moving deeper into the Confederacy. Despite several subsequent attempts by the pro-secession Missouri State Guard to retake the state, Missouri was to remain in Union control for the duration of the war.

The Bushwhacker’s targeting of the Platte River Bridge in September 1861 occurred during a brief moment when this outcome was yet uncertain, when momentum was rapidly building with pro-Confederate forces under General Sterling Price of the State Guard. Price’s militia delivered a stunning defeat to northern troops on August 10 at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek (where Lyon became the first Union general killed in the Civil War), then advanced toward the Union battalion at Lexington. Price knew that Union soldiers routinely passed through the state by railroad, bound for Leavenworth and other Federal garrisons in Kansas, so he set his militia saboteurs to attacking rail lines in northwestern Missouri. Expecting a regiment of Federal troops aboard a westbound Hannbal and St. Joseph express train on September 3, a party of Bushwhackers burned the lower timbers of the railroad’s Platte River Bridge, 30 feet high and reaching 160 feet across the shallow stream. Its upper trestles untouched, the bridge seemed intact to the engine’s unsuspecting crew as they approached at 11:15 p.m. The train, not slowing, started onto the bridge, causing its lower timbers to shatter and collapse. The entire train--engine, mail car, baggage car, freight cars, and two passenger cars--plummeted into the river.

That night there were only a few troops among the civilian passengers, more than a hundred men, women, and children. Twelve passengers died in the crash, along with most of the crew--the conductor, engineer, fireman, and two brakemen. Among the dead was Barclay Coppack, once a member of John Brown’s army who had become a Union recruiter. Dozens of passengers were injured, some of whom died after the wreck. Silas Gordon, the Bushwhacker who likely directed the attack, went south with his followers to Platte City. Union General David Hunter, stationed at Fort Leavenworth, ordered Platte County to surrender Gordon or face consequences for harboring the fugitive. On December 16, when the city’s residents refused to comply, Federal troops burned it to the ground. Gordon was never apprehended.

This letter, written in Leavenworth City on September 6, offers an early report of the Platte River Bridge attack. Its author, William Freeland, ran a Leavenworth hotel in the 1850s but was operating a livery stable on Shawnee Street by the 1860s. In 1861 he was listed as commanding a company of Leavenworth soldiers called the Lincoln Rangers, but it is unclear whether he or the company saw combat; in 1864 he was elected to the Kansas State House. The letter is addressed to his brother, Col. James Freeland of Millersburg, Pennsylvania. Freeland writes of worsening conditions in Kansas and Missouri, coming immediately to the Platte River attack:

“the night before last the RR Bridge 9 miles east of St. Jo was burned and the cars was presipitated in to the river killing 13 or 14 persons wounding 10 or 12 others and sum of them mortally. I have just returned from the funeral of 2 young men that was brout to our city for burial they belongs to Capt. Tenason’s Co of Kansas Volunteers[.] Lt. Coppis [i.e., Coppack] a brother of the Coppis that was hung in Virginia with John Brown was one of them[.] the other was a friend of his[.] The cars was fired in to the night before[,] killing and wounding severly and they have dun that frequently during the last weaks. Now the road is intirely in the hands of the Sesessions and the track torn up in a number of places and we have not had any mail for 4 or 5 days[.] The telegraph lines are cut down and our country threatened with an invasion[.]”

Freeland goes on to describe Leavenworth’s preparations for war:

“Our people are arming as well as we can to repel the Mosurians and looking or an attack every hour[.] We have but few men and fewer arms. Our county has been draned to go south and a good many was killed at the battle at Springfield [i.e., Wilson’s Creek]. James H. Lane is intrenched at Mound City 90 miles south of here with 3000 men [Lane’s Jayhawker Brigade.] Gen Rains (se sesh general) is upon him with 7 thousand men and reportedly 24 pieces of artillery and Lane cannot have more than 6 pieces[.] Rains [General James H. Rains of the Missouri State Guard] is being reinforced daily and the reinforcements for Lane cannot get through on account of the Rail Road being in the hands of the enemy[.] If Lane cannot hold out until reinforcements can cum through Leavenworth and Fort Leavenworth will undoubtedly fall in to the hands of Rainses army as we have not arms sufficient to repell them[.] there is but 4 pieces of artillery at the fort and but one piece here and not over 6 or 8 hundred guns in both places[.]....We could raise raise 4 or 5 thousand men in this and the ajoining countys for the amergency but anfortunately we have not got the armes to arm them[.] We are organizing and training day & night.”

As it happens, Lane’s cavalry had surprised Rains and his militia at Dry Wood Creek a day before Freeland’s letter, and despite being badly outnumbered, the Jayhawkers had held their own before withdrawing to Fort Scott. And in late September General John C. Frémont marched across Missouri with 38,000 Federal troops, driving Price and his State Guard from Missouri. For a brief period, though, it seemed entirely possible that Missouri and perhaps even Kansas itself would fall to pro-Confederate forces. (Robin Beck)

Relevant sources:

Fellman, Michael 1989 Inside War: The Guerilla Conflict in Missouri during the Civil War. Oxford University Press, New York.

Gerteis, Louis S. 2012 The Civil War in Missouri: A Military History. University of Missouri Press, Columbia.

Goodrich, Thomas 1999 Black Flag: Guerrilla Warfare on the Western Border, 1861-1865. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.