To General Washington From William Hartshorne, Alexandria 5th Mt 30.98

TO GENERAL WASHINGTON – RESPECTED FRIEND – FROM WILLIAM HARTSHORNE, ALEXANDRIA 5TH MT 30. 98

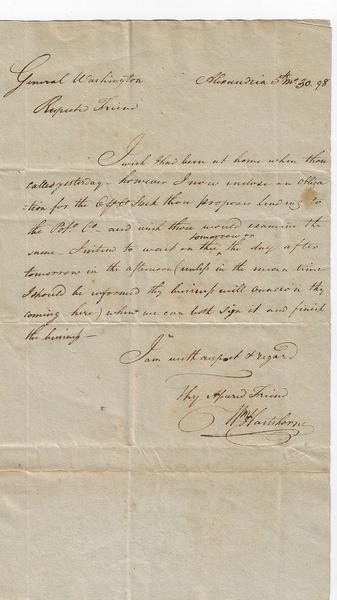

ALS 5/30/1798 William Hartshorne, treasurer of the Potomac Company (1785-1800) , Alexandria, VA to General George Washington, Mount Vernon concerning lending shares of Potomac Company stock back to the company to be used as collateral to borrow money to keep the Potomac Company infrastructure project functional. Terms 6 percent interest for 2 years. George Washington would lend 16 shares valued at $3271.36, The reverse docket / endorsement has 27 words in George Washington's hand. First image is the Wm Hartshorne letter, second is a detail of Washington's handwritten endorsement of the transfer, although not his signature.

The Potomac Company was created in 1785 in the hope of improving the Potomac River for commerce and navigability. Its goal was to build five skirting canals around the major falls of the Potomac opening the river to commercial bulk goods traffic from the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay to Cumberland, Maryland in the Cumberland Narrows notch leading west across the Alleghenies, where it intersected Nemacolin’s Trail near Braddock’s Road. Eventually this would become the first National Road which is today’s U.S. Route 40. When completed, bulk goods could ship by wagon out of the Pennsylvania and Virginia Alleghenies plateau country downhill to the river port where the canal allowed boats and rafts to float downstream towards Georgetown, a significant part of the time on the Potomac River, The company had been championed by prominent men of both Maryland and Virginia, including George Washington, the company’s first president, as well as an investor in the company. Tobias Lear, Washington's personal secretary, was its chairman for a period. Other principals of the company included Thomas Johnson of Maryland.

“As energetic men all along the Atlantic Plain now took up the problem of improving the inland rivers, they faced a storm of criticism and ridicule that would have daunted any but such as Washington and Johnson of Virginia or White and Hazard of Pennsylvania or Morris and Watson of New York. Every imaginable objection to such projects was advanced—from the inefficiency of the science of engineering to the probable destruction of all the fish in the streams. In spite of these discouragements, however, various men set themselves to form in rapid succession the Potomac Company in 1785, the Society for Promoting the Improvement of Inland Navigation in 1791, the Western and Northern Inland Lock Navigation Companies in 1792, and the Lehigh Coal Mine Company in 1793.” Archer B. Hurlbert, 1920, Paths of Inland Commerce, Chapter III.

In 1784, a year after the Treaty of Paris was signed, George Washington and Horatio Gates traveled to Annapolis to seek the state's assent to the project. Washington urged Virginia Governor Benjamin Harrison to bring the matter to the Virginia Assembly, citing the "commercial and political importance" of the project. Washington's formidable reputation in the U.S. during the time after the Revolution persuaded the governor to present a letter to the Virginia Assembly asking for support for the project. The Virginia Assembly appointed Washington, Gates, and Thomas Blackburn commissioners to seek Maryland's agreement. Washington's subsequent visit to Annapolis was successful and led to the incorporation of the Potomac Company in 1784 Maryland and 1785 in Virginia.

The Potomac Company originally wanted to hire only free labor, but due to the shortage of labor, the directors hired free, indentured, and slave labor to build the locks and canals and deepen the river. James Rumsey, a well known for his work with steam-propelled riverboats, was hired as the project's chief engineer.

Constant legal issues and the decline in public confidence in the project led to a more difficult economic position because the Potomac Company relied on individually buying shares for funds. Maryland and Virginia continued funding the Potomac Company's project beyond the original contract. However, even continued investment by Maryland, Virginia, and some individuals could not offset growing expenses due to poor technical advice, labor problems, poor planning, and incessant repair work. The work was stop and go because of the continuous need to raise more money. At many points in the project's history all work would stop as the company begged for economic assistance, settled lawsuits, and revised its plan.

After 21 years, the Potomac Canal and its assets were sold to the to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company. Its failure being attributed to a lack of federal support and oversight.

Sources: Wikipedia; Founders On Line.

Text in full:

Alexandria 5th mo 30. 98

General Washington

Respected Friend

I wish I had been at home when thou called yesterday – however I now enclose an obligation for the Pt Co. Stock thou proposes Lending to the Poto. Co. and wish thou would examine the same. I intend to wait on thee tomorrow or the day after tomorrow in the afternoon (unlefs in the mean time I should be informed thy businefs will occasion they coming here) when we can both Sign it and finish the businefs.

I am with respect & regard

Thy ____ Friend

Wm Hartshorne

(Verso in the hand of George Washington)

From The Treasurer of The Potomac Comp’y 30th May 1798. Enclosing Deed of Conveyance of 16 Shares in Said Company for the Sum of $3271 36/100 Money Cash.

A rare and important document relating to 18th century transportation infrastructure. Very legible and in very fine condition.